Bedsharing and Intimacy in the Privy Chamber of Elizabeth I

Here’s the main part of an article contributed to Alison Morton’s Roma Nova blog – the text appears in full here

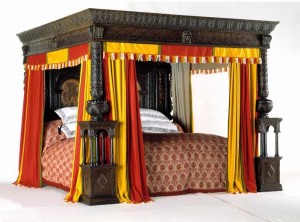

Four hundred and fifty years ago, people in England rarely slept alone. Beds were shared with spouses, siblings, close relatives and servants. Even strangers shared beds such as the Great Bed of Ware which could reputedly accommodate ‘at least four couples’.

The sleeping habits of Elizabeth I were no exception; as queen she never enjoyed solitude in her bedchamber. Even as a princess her bedroom was often invaded. The frequent forays into her chamber by her stepfather, Thomas Seymour, when she was only a young teenager, became the subject of investigation during the reign of Edward VI, and led in part to Seymour’s indictment for treason and his later execution. Speculation never completely faded that she may have been violated during one of these romps in which Seymour would ‘strike her upon the back or buttocks familiarly’ or, if he found her in bed, pull back the curtains, sometimes when both parties were in a state of undress, and ‘make as though he would come at her’. After Seymour’s fall, Elizabeth was kept under closer scrutiny, and once she was crowned queen she was never left alone.

In the Privy Chamber of Queen Elizabeth there was in fact no privacy. The Queen always slept with one of her ladies, either on a truckle bed alongside or actually in bed with her. There was never any suggestion that such intimacy was unseemly, or raised the kind of sexual innuendo that we might wonder at today. The Queen’s constant attendance by her ladies was considered essential at all hours of day and night, even during the most personal aspects of her daily routine. Elizabeth’s ladies were responsible for preserving her safety, honour and well-being, and perpetuating the image of her as Gloriana: magnificent and powerful, both chaste and fertile.

The ‘Ermine’ Portrait of Elizabeth I, attributed to Nicholas Hilliard, showing the ermine as a symbol of purity. Protecting the Queen’s reputation for chastity was one of the most important duties for those ladies who shared her bedchamber.

At any one time there would typically be around twenty female attendants in post, ranging from Chamberers (little more than chambermaids), to the well-born Ladies, Gentlewomen and Maids of the Privy Chamber, to the Maids of Honour (noble born unwed girls under the supervision of the Mother of the Maids). They saw Elizabeth at her most vulnerable and were far closer to her physically than any of the Queen’s statesmen and courtiers, including favourites such as the Earl of Leicester, Sir Christopher Hatton, Sir Walter Raleigh and, later, the Earl of Essex. Unless the more lurid rumours about her uncontrolled sexual appetites are to be believed, the Queen could only ever dream of consummated love with these men. In reality, having carnal relations with any man outside marriage would have put Elizabeth’s sovereignty and the security of the realm in grave jeopardy; it is most unlikely she ever succumbed to temptation in this way. It was with her ladies that Elizabeth went to bed.

So what went on in the Queen’s bedchamber when Her Majesty was within and the Esquires of the Body guarded the doors? In Elizabeth’s Bedfellows Anna Whitelock sheds light on this inner sanctum. Having been disrobed and unveiled; divest of her jewels, wig and gloves; the Queen’s ladies would help her wash her face and feet and then put on her nightgown: a garment of rich fabrics lined with shag, plush or fur (a gown she often wore informally well into the morning). Lastly Elizabeth would climb into her bed ‘beneath silk sheets embroidered with her royal arms and Tudor roses’ which her ladies would have warmed with pans of hot coals after checking the mattresses ‘for fleas or bugs or anything more sinister, least any would-be assassin had hidden… deadly items.’ The Queen lived under constant threat, and even in her bedroom she was never completely free from danger; there were several plots to kill her that involved attacks while she was in the Privy Chamber. Little wonder that she was frightened of the dark and often found it hard to go to sleep. If Elizabeth was feeling troubled or melancholy then her ladies would endeavour to settle her with light entertainment, perhaps music, singing or reading, then the shutters would be closed, the fire banked up, prayers said and the doors locked beyond which the guard stood watch.

Elizabeth Vernon, Countess of Southampton, one of Elizabeth I’s chief maids of honour, in the process of dressing, with her ruff and wired jewels hanging from a curtain, and her jacket loose to show her pair of bodies or bodice. On the table is a casket, ropes of pearls, carcanets (necklace collars), and jewelled pendants, together with a pin cushion showing the hundreds of pins needed to secure the pleats and fastenings of an Elizabethan lady’s clothes.

A good part of the Queen’s day was spent simply dressing and undressing. According to Janet Arnold in Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d, ‘It would have taken at least an hour to set a starched ruff and pin the flounce around the edge of a drum-shaped farthingale.’ After the Queen’s damask quilt bodies stiffened with whalebone were laced over her smock (beneath which she may well have worn drawers if these can be described as ‘a pair of double linen hose’), she would have donned silk stockings and garters, and then a petticoat, usually over a farthingale and busk, and on top of all this would be secured a heavy velvet or satin gown, often covered with braid and tiny gems and densely embroidered, or, if occasion demanded, she would wear state robes of ermine and velvet which might require four maids to help carry the train. Her hair would be combed, and her wig and headdress carefully arranged, along with her veils and ruff or wired collar, and sumptuous pearls and precious jewels. As accessories she would carry a purse, handkerchief, gloves and fan, and a girdle with yet more items hanging from it such as scissors and pen-knife, along with a pomander to provide fragrance, complementing the sweet bags impregnated with perfume which would have been laced into her clothes. If Elizabeth wished to share her worries or fears with anyone it would probably be with one of the ladies who spent hours assisting her to look the part of a queen every day.

Gloves of Elizabeth I which would probably have been perfumed with ambergris mixed with a fatty base and smeared on the inside of the gloves to keep her hands soft

From helping Elizabeth to wash and dress, apply her makeup and style her hair, to tasting her food, providing physic if anything ailed her, to attendance at the close stool, the Queen’s ladies were always nearby, observing, assisting and protecting. Whitelock describes how they prepared the cosmetic that Elizabeth wore like foundation to keep her face looking white: a ‘concoction of egg-white, powdered eggshell, alum, borax and [white] poppy seeds mixed with mill water and beaten until a froth stood on it three fingers deep.’ Her ladies even provided the ‘vallopes of fine holland cloth’ which were likely to have been used as menstrual cloths attached to ‘girdles of black Jeane silk made on the fingers garnished with buckles hooks & eyes whipped over with silk.’ Every aspect of Elizabeth’s life was watched over and noted. In theory, the Queen’s power was absolute within the borders of her domain, but one thing she could never do was close the door for more than a moment of solitude.

References

Elizabeth I & Her People – Tarnya Cooper

Elizabeth’s Bedfellows – An Intimate History of the Queen’s Court – Anna Whitelock

Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d – Janet Arnold

The Women Who Served Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth: ladies, gentlewomen and maids of the privy chamber, 1553-1603 – Charlotte Merton (University of Cambridge thesis)